NIKKI GIOVANNI

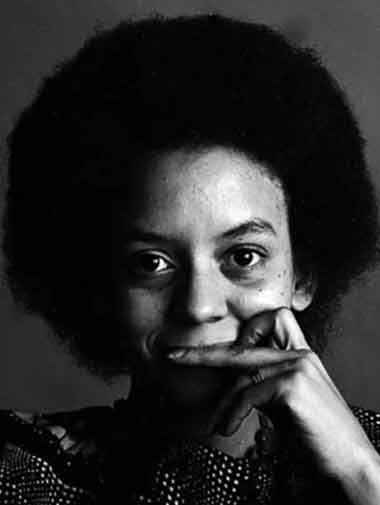

Yolanda Cornelia “Nikki” Giovanni, Jr. was born in Knoxville at Knoxville General Hospital on June 7, 1943. Her family soon moved to Cincinnati, but Nikki returned to Knoxville every summer to visit her grandparents at 400 Mulvaney Street (now Hall of Fame Drive). In 1958, Nikki returned to Knoxville, living with her grandparents and attending Austin High School on Vine Avenue (now Vine Middle Magnet School). In 1960, she enrolled in Fisk University in Nashville. Four years later, her grandmother was forced to move from Mulvaney Street due to the city’s “urban renewal” plan. Many civic buildings and parking lots were placed where the thriving African American neighborhood was once centered. Nikki’s grandmother died in 1967, and the trip to Knoxville for the funeral and the immense sense of loss led to Nikki writing what would become her first book Black Feeling Black Talk, which contains her famous poem “Knoxville, Tennessee.” Giovanni pursued graduate studies at the University of Pennsylvania and Columbia University before publishing Black Feeling Black Talk. After decades of much celebrated publishing and teaching stints at Rutgers University and Ohio State University, in 1987 she accepted a full professorship at Virginia Tech University. Giovanni remains at Virginia Tech, where she is a University Distinguished Professor.

Giovanni has received numerous awards and accolades during her celebrated career, including multiple NAACP Image Awards, the Langston Hughes Award for Distinguished Contributions to Arts and Letters, the Rosa Parks Women of Courage Award, the Outstanding Woman of Tennessee Award, and over twenty honorary degrees from colleges and universities around the country.

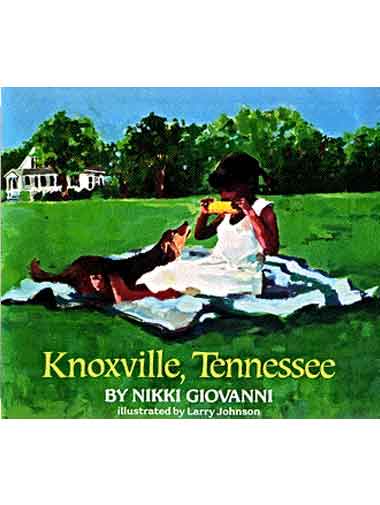

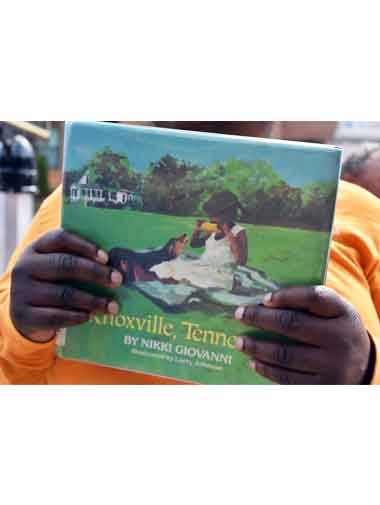

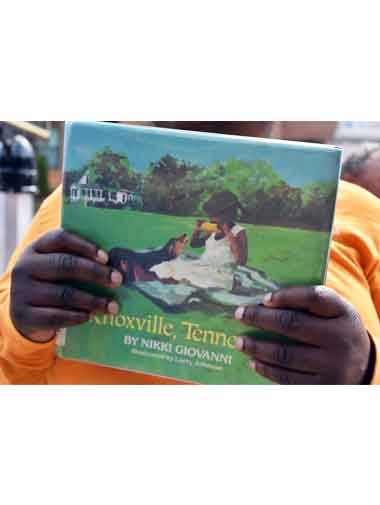

Giovanni has written several collections of poetry, autobiographies, children’s books (including an illustrated book “Knoxville, Tennessee”), and nonfiction.

Some of Giovanni’s notable publications are:

• Black Feeling, Black Talk (1968)

• Black Judgement (1969)

• Selected Poems of Nikki Giovanni (1996)

• Love Poems (1997)

• Blues For All the Changes: New Poems (1999)

• Quilting the Black-Eyed Pea: Poems and Not-Quite Poems (2002)

• The Collected Poetry of Nikki Giovanni: 1968-1998 (2003)

• Acolytes (2007)

• Bicycles: Love Poems (2009)

• Chasing Utopia: A Hybrid (2013)

• A Good Cry: What We Learn From Tears and Laughter (2017).

As her 1968 poem “Knoxville, Tennessee” demonstrates, Giovanni has a long-standing attachment to the Knoxville of her youth, when she spent summers at her grandparents’ home on Mulvaney Street (now Hall of Fame Drive). The poem evokes memories of comfort, love, and fellowship that is contrasted with the troubles in the world of the late 1960s.

Knoxville, Tennessee

I always like summer

best

you can eat fresh corn

from daddy's garden

and okra

and greens

and cabbage

and lots of

barbecue

and buttermilk

and homemade ice-cream

at the church picnic

and listen to

gospel music

outside

at the church

homecoming

and go to the mountains with

your grandmother

and go barefooted

and be warm

all the time

not only when you go to bed

and sleep

These memories have always stood in relation with the uglier aspects of US culture, including racism and resistance to the civil rights movement, as well as the “urban renewal” in Knoxville that devastated the community of Giovanni’s childhood, a “renewal” that evicted longtime residents and uprooted long-standing neighborhood networks. In 2020, Giovanni voiced her support of Vice Mayor Gwen McKenzie’s proposal asking the city to apologize for its destruction of this thriving black neighborhood and the erasure of its presence in the city. McKenzie’s proposal also asks for the city to fund grants aimed at acknowledging the irreparable damage “urban renewal” caused to Knoxville’s black communities, which Giovanni also supports. She commented in 2020, “Apologizing isn’t going to get it.” For a more detailed account, see Allie Clouse’s article from December 10, 2020 published in the Knoxville News-Sentinel here.

Giovanni revisited her childhood memories and the city’s destruction of the places of the memories in a 2020 poem “3-1593 400 Mulvaney Street,” published in Bon Appetit here. The poem provides an intimate and tender description of her grandparents’ house and the strong sense of family that existed within the walls of the house. But, it also contrasts these memories with the knowledge that they will soon be lost forever, through the passing of her grandparents and the city’s destruction of the community that is such a large part of her memories of the house. The poem ends with this theme—how the pleasant memories become hard to disentangle from the brutal razing of the neighborhood that nurtured them:

[T]he only telephone number I remember even now

Is 3-1593.

I knew when I dialed he was gone

And all that I knew of love

Would also be buried

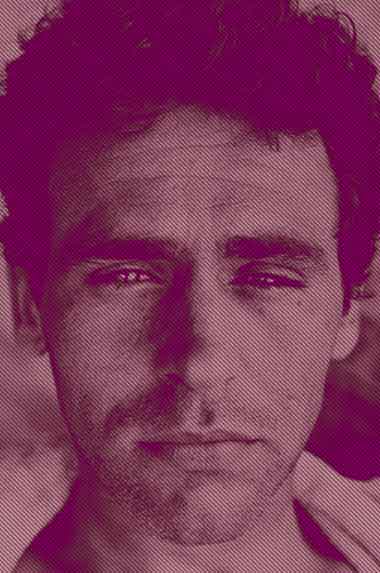

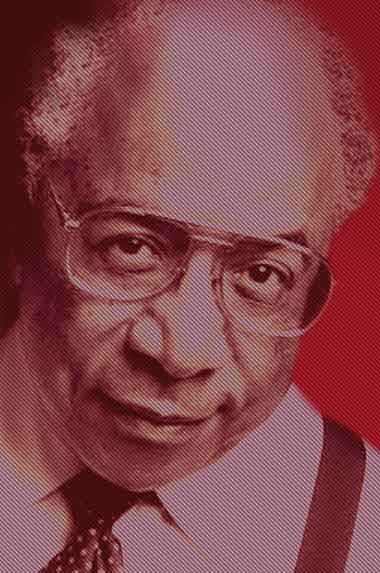

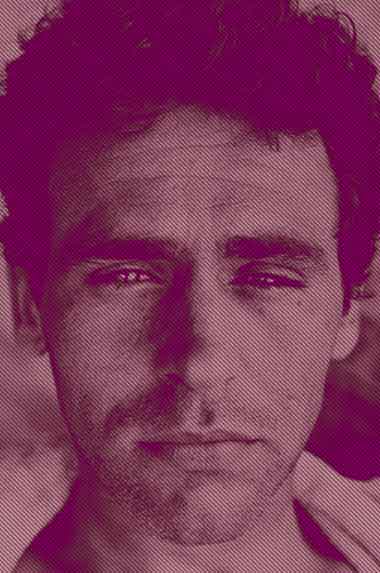

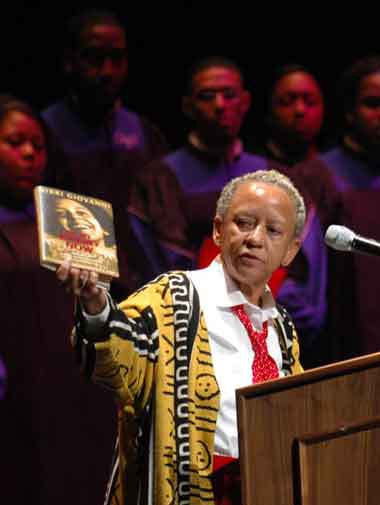

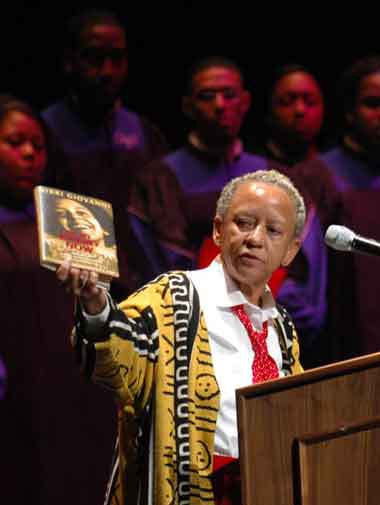

Giovanni at the Tennessee Theatre in 2007. The Knoxville-born writer and poet, who because of her race was not allowed to enter the theater in her youth, presented “On My Journey Now: Looking at African-American History Through the Spirituals.” Her appearance was sponsored by the University of Tennessee Center for Children’s and Young Adult Literature, photo and caption from News Sentinel.

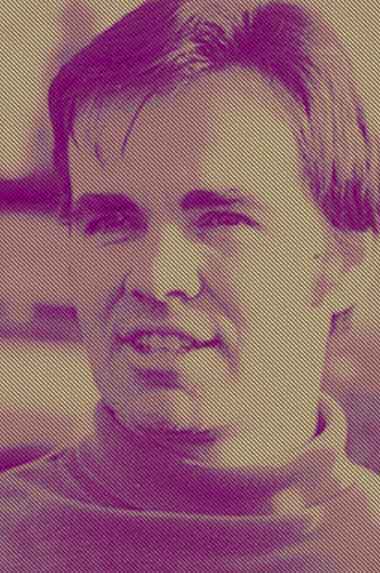

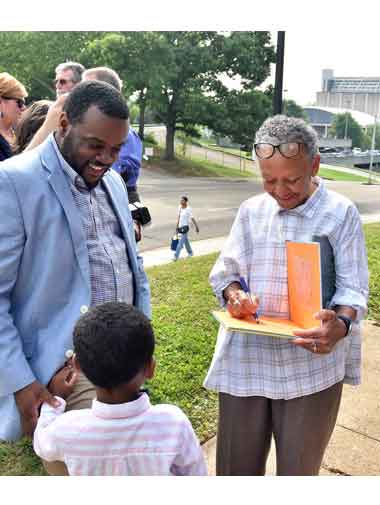

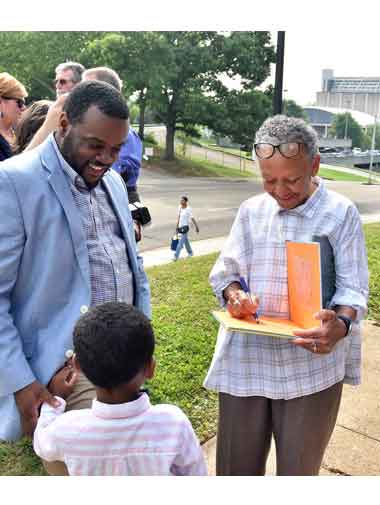

Giovanni autographs a book for four-year-old Ellison Garnes. He is pictured with his father, Ed Garnes, who was introduced to Giovanni by his mother, Carolyn Garnes, photo and caption from News Sentinel.

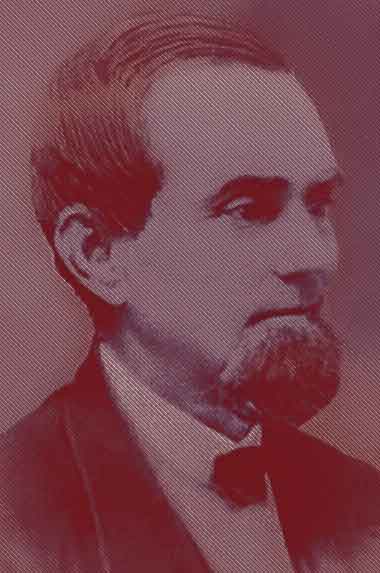

The cover of Nikki Giovanni’s book "Knoxville, Tennessee," illustration by Larry Johnson, photo and caption from News Sentinel.