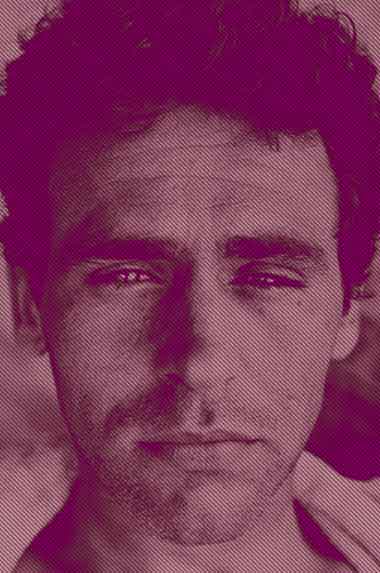

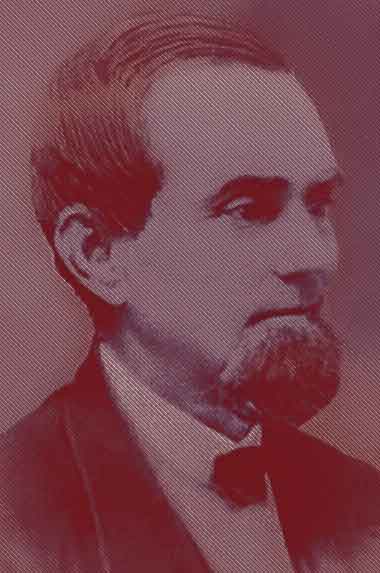

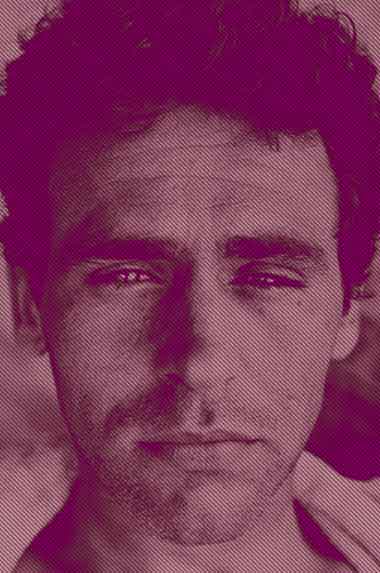

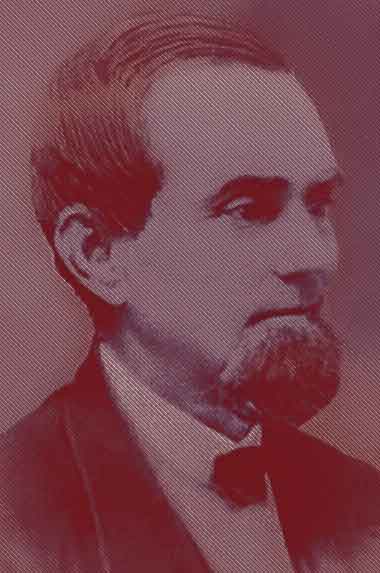

George Washington Harris

George Washington Harris was born on March 20th, 1814 in Allegheny City, Pennsylvania. At five years old Harris moved to Knoxville with his newly married half-brother, Samuel Bell, who was a metalworker and established a metal shop on what is now Market Street. Harris later farmed a piece of land in Blount County where he wrote his famous stories about Sut Lovingood, published in the New York weekly newspaper Spirit of the Times. These short pieces were later compiled into Sut Lovingood’s Yarns. Harris died mysteriously from an incident on a train in 1869.

After moving with his half-brother from Allegheny City, Pennsylvania to Knoxville, George Washington Harris received very little schooling, no more than 18 months spaced over a period of 3 years. In his teens he became the captain of a steamboat called The Knoxville that relocated Cherokee Indians westward, and was regarded for his independent character and leadership in this role. After he quit steam boating, he bought farmland on credit in Tucaleeche Cove at the “gateway” of the Great Smokey Mountains and married Mary Emiline Nance in 1835. On this piece of land in Blount County, Harris first began writing political pieces for the Knoxville Argus and Commercial Herald and the Democratic party in East Tennessee. He published comical works in the New York-based weekly Spirit of the Times. These sketches displayed the customs and dialect of rural culture—the most famous being “nat’ral born durn’d fool”—published in 1854. This story depicts comical folk tales of a backwoodsy teen named Sut Lovingood.Harris subsequently wrote a serious of tales surrounding Sut, which were compiled into Sut Lovingood’s Yarns and published in 1867. In 1868, Harris published “Bill Answorth’s Quarter Race,” supposedly based on Harris’ own experience in Knoxville as a jockey at Mr. Nance’s racetrack. Before Harris’ mysterious death in 1869, he published a jarringly prophetic piece titled “Well! Dad’s Dead!” and had written a sequel titled “High Times and Hard Times.” Harris went to Lynchburg to publish the sequel and carried the manuscript on board the returning train to Alabama, his home at the time. The train was passing through Bristol when Harris fell to the ground unconscious. The train stopped in Knoxville at the station across the street from a railroad dinner house “with a restaurant and a whiskey bar, it was just the sort of place that George Washington Harris hated” (Neely 48). Harris was carried to the hotel where a doctor examined him. There, Harris muttered his last word—“poisoned.” Some have speculated that the political writing of much of his newspaper writing made him enemies. Harris’s unpublished manuscript was never found. After his death, the Knoxville Press and Herald attempted to help bring clarity to the cause of his death:

In behalf of a community, who deeply deplore the death of Captain Harris, and who shudder to think of his horrible, lonely ride in a railway train, without one pitying glance or gentle hand to soothe his dying moments, we ask that whatever facts in the possession of any one, tending to explain this most mysterious death, be published, that the world may know, whether Capt. George W. Harris, died by the stroke of his God, or the poisoned chalice of a wicked man. (Dec. 1969) The mystery was never solved.

NOTABLE WORKS:

• “Sporting Epistle from East Tennessee”

• “A Snake-Bit Irishman”

• “A Sleep-Walking Incident”

• “Playing Old Sledge For the Presidency”

• “Love-Feast of Varmints”

• “On the Puritan Yankee”

• “Bill Answorth’s Quarter Race”

• “Well! Dad’s Dead”

• Sut Lovingood’s Yarns

KNOXVILLE LOCATIONS:

• Samuel Bell’s Metal Shop

(At the corner of Main and Prince [now Market] streets.)

• The Atkin House

The boarding house, the Atkin House (not to be confused with the subsequent Atkin Hotel, which was built on the same location in 1910 and later demolished to make room for parking lots around the Regas Restaurant) is the site of George Washington Harris’ mysterious death. Here Harris was examined by a Dr. Kraus and pronounced to have no hope. On the ground of this boarding house, George Washington Harris muttered his last word—“poisoned.”

• First Presbyterian Church

George Washington Harris served as an elder of Knoxville’s First Presbyterian Church and buried two of his children there. Gravesites of young Harriet Josephine Harris and George Harris can be found in the old cemetery adjacent to the church, inscriptions barely legible from the passing of time.

• Andrew Johnson Hotel

In the 1830s, close what was later to become the iconic Andrew Johnson Hotel (which was not completed until nearly a century later in 1929), George Washington Harris boarded with his father-in-law Peter Nance. During Harris’ time here, he was devoted to politics and the Knoxville Democratic party.